By Jill Tucker

By Jill Tucker

A year ago, Gaby Castro would show up at Mission High School not knowing whether she’d be able to get to her classes that day.

If the one elevator wasn’t working, a weekly occurrence, Castro would be stuck on the school’s second floor – her wheelchair unable to navigate all the 27 level changes scattered throughout the 84-yearold building.

And even if the elevator was working, Castro still couldn’t get to many parts of the campus, including a gym and an auditorium.

Now, about a year and $18 million later, the 18-yearold senior can get wherever she wants, whenever she wants at school.

“Now it’s, like, so perfect,” Castro said.

In San Francisco, the district has budgeted about $255 million to ensure that about 90 schools meet Americans with Disabilities Act requirements by 2012.

A federal judge is overseeing the work – everything from ramps and water fountains to scattered seating in auditoriums – to ensure that San Francisco schools adhere to a 2004 legal settlement correcting a lack of disabled access in the schools.

The Lopez case forced the district to put ADA access over everything else – sometimes leaving failing roofs or faulty boilers for later.

“It forced upon the district a legal settlement with very, very strict guidelines and timelines,” said district Chief Facilities Officer David Goldin.

Voters have approved two facilities bonds in recent years, one in 2003 for $295 million and another in 2006 for $450 million. The district is also getting nearly $100 million in state bond money.

About 30 percent is being spent to fulfill Lopez requirements, Goldin said.

Ensuring disabled access never comes cheap, Take the controversial and costly ramp to bypass the five steps up to the historic podium in the Board of Supervisors chamber in San Francisco City Hall. The total renovation related to the ramp is estimated to cost about $1 million.

At Mission High School, the project required architects to make a five-story school built on a hill – one side of the building is 50 feet higher than the other – accessible.

Inside, the 600 doors of varying sizes and shapes had to open easily, especially for wheelchair users.

Every water fountain, every bathroom, every doorway was adjusted or completely re-done. Each of those 27 separate level changes had to be addressed.

And they had to do something about the elevator.

“This building was never built with (the ADA) in mind,” Goldin said.

The architects spent two years designing the changes. Construction took two more years, with a flurry of work during the summers. Aside from finishing touches, the work is essentially done.

There fire now two elevators – one that makes seven stops, including two stops on levels that are up or down a few steps off main floors.

“I think it’s all about equal access,” said special-education teacher Nikki Taylor. The disabled students “can go see a play. They can go to the library to check out a book.”

Upgrading to ADA standards also resulted in improvements for all students, including new bathrooms throughout the school and improvements to the historic main auditorium.

“This was really a major challenge,” said Lisa Gelfand, principal of the architectural firm Gelfand Partners, as she walked through the hallways pointing out the various ramps and ADA changes. ‘’A tremendous challenge.”

While the majority of the school’s 850 students will never need any of the $18 million worth of ADA improvements, teachers and students say the improvements have created equality and are worth every penny.

“That’s the positive out of all this, that if you were blind or if you were mobility impaired, you have equal and free access (to) the best Mission High School has to offer,” Goldin said.

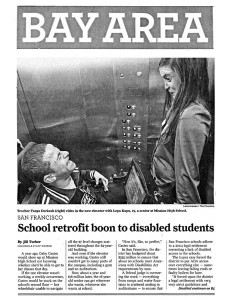

Special-education teacher Tanya Derkash shudders when she recalls how students couldn’t get to their regular high school classes because of the elevators.

“We would go get their work and they would come in here,” she said of the second floor special-education room.

Senior Lena Kupu, 19, remembers those days.

Born with cerebral palsy, he uses a wheelchair equipped with a touch screen that allows him to type or select common words off multiple screens.

“I came started here our school don’t ramp everywhere,” he said, moving across various screens quickly to access the words he wanted.

Then he smiled as he completed the next sentence that appeared at the top of his screen.

“This year excellent.”